So Long, Broadband Duopoly? Cable's High-Speed Triumph

[Source: ArsTechnica, by Nate Anderson, January 4, 2011]

Broadband users have long been skeptical of the duopoly situation in the US Internet market, which often feels like “pick your poison”: telephone company or cable company. "Where's the real competition?" they cry, pointing to other countries with healthy ISP markets thanks to regulated line-sharing or even direct government control of the underlying fiber infrastructure (Australia's new plan). But will they one day look back at the US duopoly situation with something like longing?

When the Federal Communications Commission rolled out its National Broadband Plan last year, it shied away from any bold calls to transform ISP competition. But it did note that the US is quickly moving to a situation where many markets have only a single truly high-speed Internet provider. To put it in the plainest possible terms, if your home isn't served by Verizon's fiber optic FiOS system, you could be looking at a local high-speed monopoly. And that monopoly will probably come courtesy of an industry routinely rated low for customer satisfaction: cable.

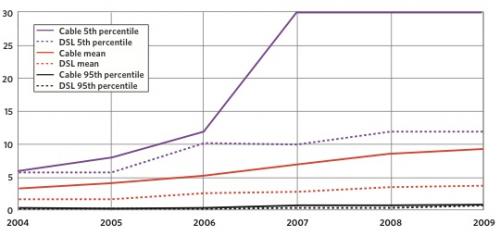

The good news is that cable operators are upgrading speeds at a rapid clip, thanks largely to the modest expense associated with doing so. But DSL, provided by telephone companies over aging copper wiring, has simply not kept pace. Here's how the National Broadband Plan frames the problem (see p. 42):

Analysts project that within a few years, approximately 90% of the population is likely to have access to broadband networks capable of peak download speeds in excess of 50 Mbps as cable systems upgrade to DOCSIS 3.0. About 15% of the population is likely to be able to choose between two robust high-speed service services [sic]—cable with DOCSIS 3.0 and upgraded services from telephone companies offering fiber-to-the-premises (FTTP)...

However, providers offering fiber-to-the-node and then DSL from the node to the premises (FTTN), while potentially much faster than traditional DSL, may not be able to match the peak speeds offered by FTTP and DOCSIS 3.0.

Thus, in areas that include 75% of the population, consumers will likely have only one service provider (cable companies with DOCSIS 3.0-enabled infrastructure) that can offer very high peak download speeds.

Some evidence suggests that this market structure is beginning to emerge as cable's offers migrate to higher peak speeds.

Broadband speeds advertised by ISPs (Source: FCC)

In an article recently put online by the Yale Law & Policy Review, law professor Susan Crawford (and former Obama administration member) argues that the “looming cable monopoly" is not just one more problem, but rather “the central crisis of our communications era.”

“When there is only one provider in each locality making available the central communications infrastructure of our time, what should the role of government be with respect to that infrastructure?” she asks. “When broadcast, voice, cable, and even newspapers are just indistinguishable bits flowing over a single, monopoly-provided fat pipe to the home, how should public goals of affordability, ubiquity, access to emergency services, and nondiscrimination be served? And what happens to diversity, localism, and the civic function of journalism?”

The "open Internet" and the "broadband Internet"

Because of the tremendous bandwidth available to cable operators, most of which now use a hybrid fiber/coax network, cable can offer these tremendous speeds while still using up only a handful of its 6MHz "channels." (DOCSIS 3.0 supports faster speeds in large part by bonding more channels together, but most systems currently bond only a few.) That leaves most of the network's bandwidth available for other uses. For now, those other uses include television, video on demand, etc. But as cable companies free up space by dumping analog channels and moving to things like Switched Digital Video (where only the currently requested channels are sent down the wire), huge new swaths of bandwidth will be freed up. For what?

“The real growth area for cable is 'broadband,'" says Crawford, “but very little of ‘broadband’ will be recognizable as Internet access. The rest of the transmissions filling the pipe will use the Internet protocol but will be thoroughly managed, monetized, prioritized, filtered, packaged, and non-executable—much like traditional cable television today. When a monopoly cable provider can allocate just two or three of its hundreds of virtual ‘channels’ to Internet conductivity and when only that provider can sell you video-strength speeds, net neutrality becomes a subsidiary issue—a tiny white bird landing on the back of an enormous hippo. Net neutrality matters, but it is a sideshow. As one content executive told me, ‘Comcast owns the Internet.’”

Crawford is a long-time advocate of net neutrality and related tech policy issues, so this might sound more than a bit hyperbolic to some observers. But one has only to listen to the ISPs themselves to see just how much they would love such a future (and it's one of the reasons they fought so hard to limit FCC oversight of “specialized services” in the recent network neutrality rulemaking).

Verizon's top lobbyist Tom Tauke put it quite plainly last summer: "Certainly nobody believes that the promise of broadband is Internet access and video, which is what we have today."

Instead, the future belongs to “‘other services’ that should be available over the broadband pipe. They need unique creativity and partnerships to make them work. It's the communications company partnering with the power company to do the smart grid. It's the communications company partnering with the healthcare provider to do heart monitoring at home. That requires a different set of rules than the rules that govern the best-effort Internet."

Everyone backing such managed services talks in terms of tele-health and the smart grid, but there's little doubt that the big ISPs would like to stay in the content distribution business (AT&T now runs an IPTV system, Verizon has FiOS TV, and the cable companies have "cable TV"). Why not a "managed service" that provides rock-solid support for Netflix streaming—if you pay an extra monthly fee?

Netflix is terrified at the prospect, and has made its worries known to the FCC, since it doesn't relish the thought of ISPs having financial incentives to serve more as a gatekeeper than a provider of a fat, fully open broadband pipe. And if that fat pipe can only be provided by one company in each market, the situation looks even worse.

Competition could come from several directions: continued advances in vectoring, pair bonding, and FTTN deployments might just keep DSL speeds competitive. Wireless, though unlikely to ever match speeds with wireline networks, could bring enough competition at medium speeds to keep abuses in check. "White spaces" broadband remains untested in the market.

But when it comes to truly high-speed Internet access, the cable companies currently have the best seat in the house. And they know it.