Libyans Turn to YouTube to Circumvent Media Blackout

[Source: GigaOm, by Janko Roettgers, February 23, 2011]

If you were ever doubtful about the disruptive power of online video, consider this: Libyan border guards have started to frisk people leaving the country for recording equipment, “systematically destroying cell phone SIM and memory cards” that could contain videos and photos of the violent clashes within the country, according to CNN’s Nick Robertson, who is reporting about the crisis from the border between Libya and Tunisia.

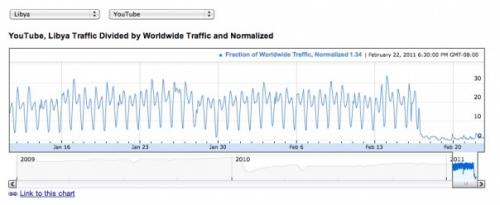

Libya also started to block access to YouTube as soon as the protests started last week, and access has been spotty at best ever since. Here’s a graph from Google’s Transparency Tool that clearly shows traffic dropping after Feb. 16, the day the uprising started in the eastern part of the country:

Many videos documenting the violence in Libya nonetheless find their way to YouTube. A Google spokesperson said on Tuesday that more than 9500 videos tagged “Libya” have been uploaded to the video site in the week since the beginning of the uprising.

YouTube has been experimenting with the news curation startup Storyful to make sense of these videos and highlight some of the submissions as part of its Citizentube project, and Storyful Editorial Director David Clinch told me much of the video has been uploaded with the help of Libyan expats. “Most are mirrored,” he said. Libyans occasionally have access to services like Facebook or Twitvid, and volunteers immediately take clips available on those services and upload them to YouTube.

Libyans seem to be quite aware that online video is playing a huge role in telling their side of the story, and they’re going to great lengths to circumvent the media blackout. “They are all pushing the videos out so the world can see them,” Clinch told me, adding that some clips are even “physically crossing borders.” Footage makes it out of the country in the luggage of refugees, despite security checks like the ones reported by Robertson, and Time Magazine even reported about organized sneakernets this week. It quoted one opposition member saying:

“We sent my brother and his friend to Marsa Matruh [in Egypt] to use the Internet. I went to Egypt every day to give him a flash disk full of media from Tobruk, al-Baida, Benghazi. They were videos from mobiles. Not just mine. We made copies, went to the Egyptian border at Salloum and gave it to someone there…”

Storyful is using contacts within Libya as well as expats to vet and contextualize the footage coming out of the country. That process can be complicated by the fact that some of the footage appears online without any meta-data whatsoever, but Clinch said that he has “a very high degree of confidence” in the videos curated by his company. CNN, Al-Jazeera and others have been using the very same footage that first showed up on YouTube to report about the situation in Libya, and Clinch said that in a few years, YouTube may be a prime source to learn how the uprising in Libya started.