Broadband Can Close the Education Loop

[Source: Daily Yonder, by Sharon Strover and Nick Muntean; March 8, 2010]

Education increases chances for employment. Distance learning increases educational opportunities for rural residents. Rural development these days means broadband and online classes. We realize that outmigration among rural youth is a problem for many rural communities and there is some hope that comprehensive broadband build-out in rural areas could provide rural places with the infrastructure they need to provide the jobs that would give those young people a way to stay.

We realize that outmigration among rural youth is a problem for many rural communities and there is some hope that comprehensive broadband build-out in rural areas could provide rural places with the infrastructure they need to provide the jobs that would give those young people a way to stay.

But broadband build-out alone will not solve the employment woes of rural areas. As long as there continues to be a marked gap between the education levels of urban and rural citizens, we cannot expect highly-skilled, well-paying telework jobs to transfer to rural areas of their own accord.

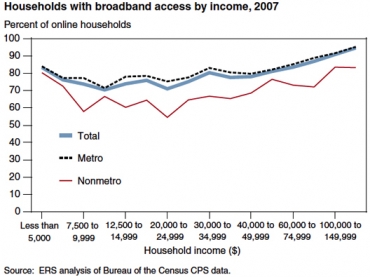

There is the possibility, however, that rural broadband build-out could not only facilitate the infrastructure needed to bring telework positions to rural communities, but also provide the means for rural residents to enroll in distance learning courses that will help them to become more competitive in the national and global marketplace.

Why distance learning? Historically, rural communities have sought to close the rural/urban education gap by sending their most promising young students to far-away colleges and universities for post-secondary instruction. On the face of it, this is a seemingly sound plan. However, this strategy has a few crucial shortcomings.

First, most of the time, upon finishing college, those freshly educated young people don't move back to the farm. Some students never can afford to pay for college far away and consequently don’t get a college education at all. And, finally, some students may not be ready for a four-year school and need additional preparation. Distance learning—where students take online courses from accredited institutions—could counter these dilemmas, and allow students to broaden their intellectual horizons while remaining in the communities in which they've been raised.

But is the gap between rural and urban education levels really so significant that rural residents find themselves at a competitive disadvantage? According to the National Center for Education Statistics' 2004 data, while rural residents age 25 and older actually lead their city and suburban counterparts in terms of high school diplomas (or equivalent), and are roughly equal when it comes to the category of "some college/associate's degree," rural residents lag considerably behind their urban peers in terms of bachelor's degrees and graduate or professional degrees. Only 19.1% of the rural population has a bachelor’s or graduate degree, while the comparable figure for cities and suburban regions is 29.8% and 31.5% respectively.

While the predominance of manufacturing and agricultural jobs in rural areas often makes it difficult to justify the costs of a full four-year education, the number of jobs available in these sectors has been on the decline for decades now, a trend exacerbated during the recent economic crisis. With rural manufacturing communities being particularly hard-hit in the current recession, and the ever-increasing talk of a "jobless recovery," it is clear that rural residents should not wait for these jobs to return. They probably won't. The best plan for creating new job opportunities in rural areas is to offer national and international businesses a new type of employee, one with a skill-set and level of education equal to those found in any other region in the world.

Two vital issues remain in our discussion of distance learning: the cost of tuition and generational differences in attitudes regarding the value and effectiveness of online education. For many older individuals, online and distance learning programs carry a certain stigma. They are regarded as being somehow less effective or worthwhile than traditional classroom instruction. For younger students, however, distance learning is a fact of life, with over one million K-12 students currently enrolled in online or blended courses. For these younger students, who have grown up with online curricula, distance learning in post-secondary programs simply seems par for the course. Moreover, the quality and diversity of online curricula has never been better. For older and returning students, however, ambivalence about the quality of distance learning and a lack of familiarity with the required technology may hinder enrollment efforts. Government-sponsored public service campaigns could simultaneously raise awareness about the benefits of broadband and broadband-assisted distance learning, though this would not mitigate the fairly significant issue of the financial costs of these distance-learning programs.

For younger students, however, distance learning is a fact of life, with over one million K-12 students currently enrolled in online or blended courses. For these younger students, who have grown up with online curricula, distance learning in post-secondary programs simply seems par for the course. Moreover, the quality and diversity of online curricula has never been better. For older and returning students, however, ambivalence about the quality of distance learning and a lack of familiarity with the required technology may hinder enrollment efforts. Government-sponsored public service campaigns could simultaneously raise awareness about the benefits of broadband and broadband-assisted distance learning, though this would not mitigate the fairly significant issue of the financial costs of these distance-learning programs.

Still, those who might most benefit from continuing education and distance learning are also frequently those least able to afford it. While the tuition rates of online courses are often lower than those at comparable traditional post-secondary institutions, with no guarantee of a job after graduation, the costs remain too high for many individuals, rural or urban. Many government-subsidized job training programs do not offer the convenience or flexibility of online courses, nor do they provide the employment flexibility afforded by the breadth and depth of more sustained post-secondary study. If distance learning is poised to bring considerable benefits to rural areas, what role should the government play, beyond simply ensuring that adequate broadband infrastructure exists in the first place?

Can rural communities provide the resources and support necessary to help spur greater levels of educational achievement, or must other organizations and levels of government be involved in this process?

We have made a national commitment to the notion of "No Child Left Behind" from kindergarten through twelfth grade, and the current administration supports a “Race to the Top” program to create better incentives in schools, but our collective commitment and energy curiously ends with the conferral of a high school diploma. If, as a nation, we are poised to create a true "21st century labor-force," then we need to rethink our commitment to providing accessible forms of higher education for all of our citizenry, and we need to begin that commitment where it matters most, in the rural communities across our country using the resources that broadband can bring.

Sharon Strover is director of the Telecommunications and Information Policy Institute at the University of Texas. Nick Muntean is a PhD student in the Radio-Television-Film Department at the University of Texas at Austin.