U.K. Regulators Officially Mock U.S. over ISP "Competition"

[Source: Ars Technica, by Nate Anderson; March 25, 2010]

Here's how U.S. regulators do a broadband plan: talk about competition even while admitting there isn't enough, then tinker around the edges with running fiber to "anchor institutions" and start collecting real data on U.S. broadband use.

Here's how U.S. regulators do a broadband plan: talk about competition even while admitting there isn't enough, then tinker around the edges with running fiber to "anchor institutions" and start collecting real data on U.S. broadband use.

Here's how they do it in the U.K.: order incumbent telco BT to share its fiber lines with any ISP who is willing to pay. In places where BT hasn't yet run fiber, order the company to share its ducts and poles with anyone who wants to run said fiber. In the 14 percent of the U.K. without meaningful broadband competition, slap price controls on Internet access to keep people from getting gouged.

Government regulations can't encourage innovation? That's not the way U.K. telecoms regulator Ofcom sees the world, and it takes a none-too-subtle dig at the U.S. model.

"Availability of super-fast broadband in the U.K. (some 46 percent of homes) is now ahead of most large economies where deployments have been funded commercially. In the U.S., AT&T and Verizon have upgraded their networks to cover 17 percent and 12 percent of households, respectively, while cable company Comcast is approaching coverage of around 35 percent of US households with super-fast cable broadband."

In case you're not getting the message, Ofcom is prepared to bludgeon you over the head with it.

"Aside from small urban countries with highly concentrated populations, like Singapore, the main countries which are currently leading in the rollout and take-up of super-fast broadband are those which have had significant government intervention to support deployment, such as Japan and South Korea."

We're super-fast!

Ofcom's words are part of its new proposal (PDF), released yesterday, to encourage what it calls "super-fast broadband" deployments. This is Internet access above 24Mbps, the upper limit for the most common forms of DSL, and it generally refers to DOCSIS 3.0 cable systems or fiber.

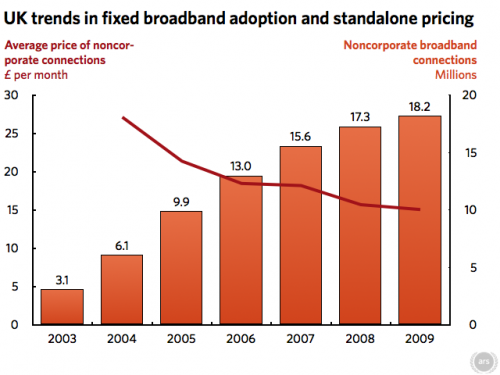

Government line-sharing rules have long forced BT to unbundle last-mile copper and make it available to other ISPs. The result has been solid competition in the U.K. (if you believe Ofcom, it is "one of the most competitive broadband markets in Europe"). The result has been lower prices.

Source: Ofcom

The new sharing rules for ducts and fiber are meant to spur investment in higher speeds. In order not to deter BT's own investment in the fiber network, Ofcom will let the company set its own prices, and it argues that prices "will be constrained by the wider competitiveness of the broadband market."

In places where BT has already rolled out fiber to the home, few ISPs would want to duplicate that effort with a fiber installation of their own; most prefer to share. But in places where BT has not deployed fiber, other ISPs might want to do so in order to gain a competitive advantage. In this case, they will get regulated access to existing in-ground cable ducting and to BT's poles for aerial fiber deployments. In 2008 and in 2009, Ofcom actually surveyed BT's ducting and concluded that nearly half of existing ducts have additional room for cabling.

Line-sharing rules haven't been a panacea for everyone. Outside of well-populated areas, some 14 percent of the country has access only to copper wire, and the only ISP is BT. While Ofcom has declined to do any price regulation in most of the country (it deregulated parts of the market in 2008), it does intend to apply "locally specific price controls" to prevent BT from abusing a monopoly position.

Ofcom's basic approach has much in common with the FCC-commissioned report from Harvard that came to similar conclusions about the importance of government involvement with the line-sharing rules. The FCC staffers who wrote the recently released National Broadband Plan were certainly aware of all this information, but they also believe that the U.S. is a special case.

Unlike in most European countries, for instance, the U.S. has a huge cable infrastructure, providing a much different regulatory environment than states with a single incumbent telephone company and little cable infrastructure. (Note that this isn't really true of the U.K., however, where 46% of the country can get cable.) While mandated line-sharing might have created competition 7 to 10 years ago, the broadband team simply doesn't believe it would work today. The big ISPs have economies of scale, the pool of brand-new Internet subscribers is much smaller, and few companies have been lobbying the FCC with promises of massive investment if the agency changed its stance.

So when did the U.K. start mandating unbundling? As recently as 2005—and in the five years since, more than 6 million residents have taken advantage of the rule to use an alternate ISP.

The problem is that, moving forward, U.S. Internet users who don't live in FiOS territory will quickly have even less competition than they do now. No major telephone company has announced plans for ambitious fiber deployments, even as cable operators raced ahead with (cheap) DOCSIS 3.0 upgrades. Even the National Broadband Plan admits that within a few years, only 15% of Americans will have more than one option for truly high-speed broadband.

Experiments like those currently underway by Google and universities like Case Western Reserve in Cleveland may show Americans the benefits of a fiber-optic network open to any ISP, and perhaps seeing what such a network might look like will galvanize some kind of change in the competitive landscape. But for now, and for the foreseeable future, "competition" is not a strong suit of truly high-speed Internet access in most of the U.S.