The Digital Divide Will Ensure a Broadband Ghetto

[Source: GigaOM, by Stacey Higginbotham; March 27, 2010] If you live in New York City or in any of the heavily populated and wealthy areas of the Northeast, you likely have access to some of the fastest broadband speeds available in the country. If you live in a suburb of Austin, Texas, however, you’re offered speeds some six times slower for about half the price. And as the technologies race ahead for network access, ISPs with fiber to the home and cable-provided Docsis 3.0 service are going to surpass the speeds that providers using old-school copper and even wireless can offer.

If you live in New York City or in any of the heavily populated and wealthy areas of the Northeast, you likely have access to some of the fastest broadband speeds available in the country. If you live in a suburb of Austin, Texas, however, you’re offered speeds some six times slower for about half the price. And as the technologies race ahead for network access, ISPs with fiber to the home and cable-provided Docsis 3.0 service are going to surpass the speeds that providers using old-school copper and even wireless can offer.

Which means that while some people will be living in the 21st century, great chunks of the country will be subsisting on the 2010 version of dial-up. Don’t believe me? Verizon has tested a tech that requires software upgrades to deliver a 10 Gbps connection that’s shared among 32 homes. Meanwhile, technologies such as the next generation from AT&T are going to require swapping out gear at the node and inside your home so the companies still using copper can squeak up to speeds that most analysts doubt will even reach 100 Mbps. That means a hundred-fold disparity in connection speeds. Holy cow.

We’ve addressed this in stories, when FCC chairman Julius Genachowski came to visit our offices and even in conversations with service providers. It’s the key reason the U.S. isn’t competitive with other countries when it comes to the rapid deployment of next-generation networking technology. So we think it’s a big issue. The FCC even thinks it’s a big issue. Google thinks it’s a big enough issue that it’s going to spend hundreds of millions of dollars to build a shared, experimental fiber-to-the-home network — and embarrass the ISPs and the government in the process.

To quote the Google blog: “After all, you shouldn’t have to jump into frozen lakes and shark tanks to get ultra high-speed broadband.” Oh, but that’s what people are willing to do because the ISPs are so focused on the short-term bottom line to spend billions (yes billions) on big pipes. When I talk to many ISPs, the No. 1 reason they give me for the lack of investment in faster infrastructure is that users don’t want it. There’s no killer app driving demand.

I’d buy that if ISPs were investing in research to find those killer apps, or weren’t actively seeking to whittle down connection speeds with tiered pricing plans or caps. But consumers are finding killer apps of a sort — only those killer apps interfere with the pay-TV side of the equation for cable guys and telcos that have invested in IPTV infrastructures. But even if the idea of another we-have-more-HD-channels-fight thrills you, the truth of the matter is that competition in broadband speeds will bring about the connected home.

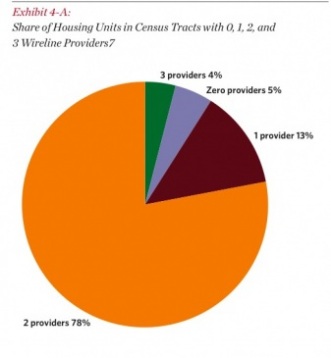

No longer will just your computer always be on; your thermostat, your television, your appliances and your links to loved ones will be, too — and possibly throughout every room of your home. But that’s not going to happen for those without fat pipes. Which is why I and others found the National Broadband plan so disappointing. While it gets a lot of things right when it comes to boosting broadband adoption, it doesn’t really help drive innovation or ensure competition. And the plan’s authors are aware of this. They offer the salve of data as a means to possibly protect consumers from overcharging and to shame providers into offering better service, but that’s going to require an activist FCC like the current commissioners are, and in a few years, who knows if that will be the case. And I am as excited about faster mobile broadband as anyone (maybe more), but mobile data isn’t going to replace wireline broadband — nor should we be content with those speeds.

And the plan’s authors are aware of this. They offer the salve of data as a means to possibly protect consumers from overcharging and to shame providers into offering better service, but that’s going to require an activist FCC like the current commissioners are, and in a few years, who knows if that will be the case. And I am as excited about faster mobile broadband as anyone (maybe more), but mobile data isn’t going to replace wireline broadband — nor should we be content with those speeds.

I understand that having spent $19 billion building out a fiber network, Verizon would be justifiably upset over sharing its fiber with competitors. We also currently have a huge variety in our network providers that makes sharing lines difficult from both a technical and regulatory perspective. However, the type of open-shared network that Google is proposing is the fastest ways to get the U.S. big broadband quickly.

Since the FCC can’t get it done through the Broadband Plan (it isn’t even trying) and Congress decided not to get it done with the stimulus money (a few fiber projects were approved), then it’s up to the FCC and Congress to make it easier for cities to deploy their own fiber networks which can then be opened up to competition. That means making it possible to change the laws in the 18 states that make it difficult for municipalities to own fiber networks or offer competitive communications services, but will likely evolve as a states rights battle.

Right now, Google and consumer demand is our best hope for better broadband, which isn’t making me feel too great about the future. Anyone have a freezing lake I can dive into?