Fair Use Isn’t Much Good If You Can’t Afford It

[Source: GigaOm, by Mathew Ingram, June 24, 2011]

All around us, the web is enabling an explosion of “remix culture,” in which bits and pieces of text, images and video are cut and spliced to create new forms of art. Whatever you think of the specific outcomes of this process, it’s arguably a huge social benefit — and the principle of “fair use” is supposed to make that easier to enable.But as Kickstarter co-founder Andy Baio discovered when he put together an art project, “fair use” only applies if you can afford to fight for your idea in court — and if you can’t, you will fail. What does that mean for the future of the remixable web?

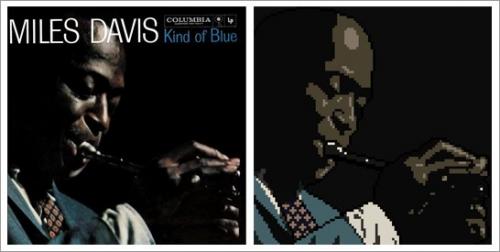

Baio, who is also a prominent blogger at Waxy.org, described in a long post on Thursday how he decided to put together a musical tribute to the jazz musician Miles Davis, by creating eight-bit — i.e., ringtone-level quality — versions of the famous album Kind of Blue. Baio carefully cleared all the licenses for the songs themselves, and even decided to donate the proceeds from the sales of his project (which was released last year) to the musicians who played on the album.

However, Baio didn’t get approval for the cover image, which was a pixellated version of the original photo of Davis, taken by the famous photographer Jay Maisel. After releasing his project — called Kind of Bloop — Baio got a legal claim from Maisel’s lawyers, who said his image represented copyright infringement. Despite Baio’s belief that the pixellated version of the image represented fair use, the blogger says he couldn’t afford to fight the lawsuit in court, and ultimately settled by paying Maisel $32,500.

[T]his is important: the fact that I settled is not an admission of guilt. My lawyers and I firmly believe that the pixel art is “fair use” and Maisel and his counsel firmly disagree. I settled for one reason: this was the least expensive option available.

As Baio’s blog post circulated around the blogosphere and on Twitter, it sparked a firestorm of criticism aimed at Maisel (which Baio tried to help snuff out). Eventually, that storm — which focused in part on the fact that the photographer lives in a 72-room New York landmark valued at $35 million — spilled over onto Maisel’s Facebook page, where hundreds of comments piled up accusing him of targeting a poor blogger. Part-way through the day on Thursday, the page was removed.

The fact that Jay Maisel is a famous and wealthy photographer (he actually bought the New York building in 1966 for $102,000) and Baio is just a blogger who helps run a startup shouldn’t have any bearing on whether what Baio did qualifies as fair use or not — but it does, because the only way to defend against such a claim is to go to court, since the burden of proof for fair use is on the defendant. And going to court is expensive.

It doesn’t help that the fair-use principle is complicated. There is no blanket “this is art” or even “this is a parody” exemption. Instead, the courts look at four factors — including the nature of the work (i.e., whether it is “transformative”) and whether it affects the ability of the creator to sell or license the original. Based on some of what Judge Pierre Leval has written about fair use, I — and plenty of others — think it’s pretty clear that Baio’s use was transformative. It altered the image both literally and figuratively for artistic purposes, and is unlikely to affect Maisel’s ability to license the original. As Baio put it:

Far from being a copy, the cover art comments on it and uses the photo in new ways to send a new message. This kind of transformation is the foundation of fair use.

But in the end, as Baio notes, none of that matters because he couldn’t afford to fight the case. Over the past decade or so there have likely been thousands or tens of thousands of similar cases — not to mention some in which home movies were removed from YouTube because copyrighted music was playing in the background — because no one wanted to (or could afford) to fight the case. And the result is that large entertainment and media entities get to dictate what is fair use and what isn’t.

This has a real impact on our society, as copyright-reform advocate Larry Lessig has said and written a number of times in his comments about the value of “remix culture,” including his 2008 book Remix. Digital content is so fluid that remixes and mashups of popular culture and mainstream content of all kinds have become a kind of second language, particularly for web-savvy young people.

My teenaged daughters, for example, experience almost every major news event via a video mashup of some kind — usually because someone makes a parody, as they did with the “Bed Intruder” and even the death of Osama bin Laden. This has become an integral part of how they experience media and content, and almost all of it is probably copyright infringement of some kind. Do we ultimately gain by stamping out that kind of thing with expensive lawsuits, or do we lose? I think it’s clearly the latter.

Post and thumbnail photos courtesy of Flickr user Dawn Endico and Andy Baio