How the Telecom Lobby Is Killing Municipal Broadband

[Source: The Atlantic, by Emily Badger, November 4, 2011]

The city of Longmont, Colo., built its own 17-mile, million dollar fiber-optic loop in the mid-1990s. The infrastructure was paid for by the local city-owned electric utility, though it offered promise for bringing broadband to local businesses, government offices and residents, too.

The city of Longmont, Colo., built its own 17-mile, million dollar fiber-optic loop in the mid-1990s. The infrastructure was paid for by the local city-owned electric utility, though it offered promise for bringing broadband to local businesses, government offices and residents, too.For years, though, the network has been sitting largely unused. In 2005, Colorado passed a state law preventing local governments from essentially building and operating their own telecommunications infrastructure.

Behind the law was, not surprisingly, the telecom lobby, which has approached the threat of municipal broadband all across the country with deep suspicion and even deeper pockets. Companies like Comcast understandably want to protect their corner on the market from competition with city-run nonprofits. What’s less understandable is the route their interests have taken: Residents and state legislators from Colorado to North Carolina have been voting away the rights of cities to build their own broadband, with their own money, for the benefit of their own communities.

This battle has largely pitted well-organized corporations against people who aren’t quite sure what they’re voting on. Such measures have now passed in 19 states. And in 2009, when Longmont put a referendum to the people asking to lift the state restrictions and return the city’s authority over its existing fiber loop, 56 percent of them said "no."

“As we’ve seen elsewhere, in the months after the election, people learned a little bit more about the issue,” says Christopher Mitchell, who directs the Telecommunications as Commons Initiative at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. “One of the quotes was, ‘Why didn’t the city tells us more about what was at stake? Because we didn’t want to basically vote for Comcast. We didn’t know Comcast was behind this ad.’”

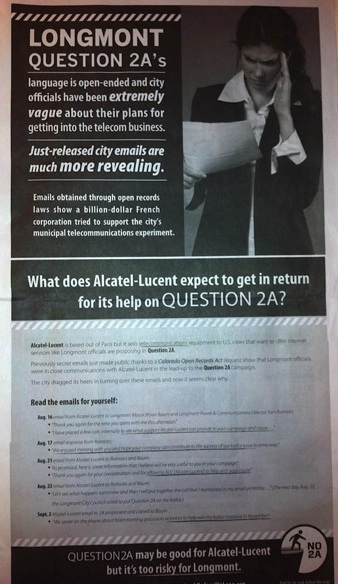

“As we’ve seen elsewhere, in the months after the election, people learned a little bit more about the issue,” says Christopher Mitchell, who directs the Telecommunications as Commons Initiative at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. “One of the quotes was, ‘Why didn’t the city tells us more about what was at stake? Because we didn’t want to basically vote for Comcast. We didn’t know Comcast was behind this ad.’”In 2009, opponents of the initiative including the Colorado Cable Telecommunications Association, of which Comcast is a major contributor, spent $250,000 – some of which went to ads like the one pictured at right – to suggest that the ballot measure would raise taxes, cost firefighters their jobs and generally drag down the city.

“So people got upset,” Mitchell says, “and started to say ‘we should vote again.’”

Which brings us to this week. After another bruising campaign – into which the telecom lobby poured another reported $300,000 – the people of Longmont voted again on Tuesday. This time, the city got its message straight, the local newspaper editorialized in favor of the measure, and every candidate also on the ballot for the mayor’s office and city council unanimously supported it.

This time the initiative passed, with more than 60 percent of people in favor.

The vote was a major victory for municipal broadband, even if it sounds like a slightly ridiculous one. Longmont didn’t vote to build a broadband network, or to raise taxes to one day build a broadband network, or even to undertake a study group to start thinking about building a broadband network. It simply voted that the city should have the right to decide what to do with largely unused infrastructure it built 15 years ago.

“Now they have the authority to make their own decisions,” Mitchell says. “It’s like they just turned 18 or 21.”

The city may opt to do nothing. Or it could provide its own broadband services to locals, directly through the city or a contracted partner. In time, it could also expand the system to reach more residents.

The vote may be a tipping point for advocates of community broadband in other cities who’ve rallied against the high prices and poor service that can come from having only one or two local providers (96 percent of households in America are served by a broadband duopoly or worse, according to the FCC). Seattle and Portland have expressed an interest in building their own networks. Chattanooga already has one. Until now, in arguing for why more communities should stay away, existing broadband providers have largely benefited from the fact that most people just don't get what all this means.

“As people become more informed on this issue, they become more supportive of the local community at least having the power to invest in this essential infrastructure,” Mitchell says. “As time goes on, it’s easier to make that case to people because they recognize how incredibly important access to the Internet is.”

But what’s to say Longmont won’t just vote again in another two years and change its mind a third time, under the spell of more telecom advertising?

“If this city council makes dumb decisions and people come to regret that or come to disagree, I would expect them to vote those people out, and new people will come in,” Mitchell says. “But I don’t think we would see an attempt to no longer be able to make adult decisions. I feel like once they’re 18, they’re not going to return the opportunity to make their own decisions.”