When Candidates Lie, What's a Political Reporter to Do?

[Source: Nieman Watchdog, by Dan Froomkin, November 30, 2011]

How journalists respond to intentional deception will be a defining feature of 2012 political coverage. Will they allow themselves to become accessories to deceptive politicians? Or will they aggressively and repeatedly expose misinformation and the people who traffic in it?

Political reporters are notoriously unwilling to call even the most outrageous, intentionally deceptive untruths what they are: lies.

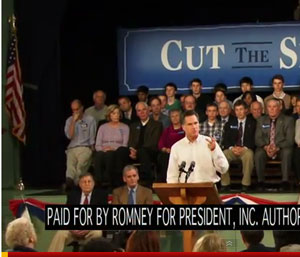

But Mitt Romney's very first campaign ad of the 2012 presidential race, broadcast in New Hampshire last week, is an indication that the year ahead may be full of them.

But Mitt Romney's very first campaign ad of the 2012 presidential race, broadcast in New Hampshire last week, is an indication that the year ahead may be full of them.The Romney ad in question used a quote from then-Senator Barack Obama in a deliberately deceptive way. "If we keep talking about the economy, we're going to lose," Obama is heard to say. He did say that, but in a context that made it clear he felt the opposite way. The full quote, from an October 2008 speech: "Senator McCain's campaign actually said, and I quote, if we keep talking about the economy, we're going to lose."

Some of the mainstream-media coverage simply noted the deception in passing, some focused on its effectiveness as a campaign tactic. What was missing was sustained coverage about the lie itself.

Experts in journalistic ethics are encouraging reporters to take a more critical posture going forward.

"I think professional journalists have an absolute obligation to make lies transparent," said Kelly McBride, who teaches ethics at the Poynter Institute.

The first step is "to do the reporting so that you can with authority point out that this is an act of deception," McBride said. With the Romney ad, that was easy; the accompanying press release provided Obama's full quote.

Step two, McBride said, is to assign blame.

"Professional journalists need to follow up and figure out who in the campaign is responsible for this," McBride said - "and keep at it."

"We have to call that sort of thing out," Geneva Overholser, director of USC Annenberg School of Journalism and a former Washington Post ombudsman, wrote in an e-mail. "Journalists did that, last week, but it seems to me it needs to have been even stronger. This was such a blatant act of deception. Treating it just like any other fact-checked ad, so many of which contain something mildly misleading, is itself misleading."

In this case, Romney himself defended the ad, telling reporters: "There was no hidden effort on the part of our campaign. It was instead to point out that what's sauce for the goose is now sauce for the gander."

There's a character question here, particularly if this kind of behavior continues, said Tom Fiedler, communications dean at Boston University and former executive editor of the Miami Herald.

"What you can do is you just continue to build a case, so that you periodically come back with a larger story that goes to the integrity of the candidate who would continue to put up ads that are clearly out of context and that sort of thing," Fiedler said.

"And that can be a major, defining piece."

Journalists also need to be aware of how easily they are manipulated by intentionally deceptive candidates.

"It's a known tactic that in some cases, a candidate will make an ad more misleading to generate controversy that will in turn reinforce the message of the ad," said Brendan Nyhan, an assistant professor of government at Dartmouth College. "In TV, it's especially easy to reinforce the message of the ad by running it over and over."

One classic dupe move is for journalists to report on the "controversy" over the deception, rather than directly address its truthfulness.

Another is to simply treat it all like a game. As Nyhan wrote in a blog post for CJR.org: "For these journalists, producing meta-level analysis of the effectiveness of deception as a campaign tactic is more important than correcting the factual record for readers."

"This all goes back to journalists' unwillingness to see themselves as strategic actors in a political game," Nyhan told HuffPost. "There's this naive professional posture that can make people tools of the campaign, if they're not careful."

And here's another problem: Nyhan's research shows that "it's difficult to convince people who don't want to be convinced that a claim is false." So journalists need to ask themselves: "Whose mind do you expect to change about what?"

"I think you have to write these stories, but you also have to be careful in putting together a story that would be convincing to someone who's not inclined to believe the correction," Nyhan said.

In the case of the Romney ad, Nyhan suggests that reporting showing even Republicans agree that the quote was deceptive would be particularly effective.

Other convincing tactics Nyhan proposed are "Getting it out of a partisan context to the extent possible" and "emphasizing documentary evidence - although we've obviously seen the limitations of that." (Even after Obama produced his birth certificate, claims that he was born abroad continue.)

As for reporters' hesitation to use the words "lie" or "liar," Charlotte Grimes, who holds the Knight Chair in Political Reporting at Syracuse University, says there's a reason for that.

"I think you've got to be as aggressive as possible," Grimes said. "We need to do that all the time." But, she added, "I think what we have a great reluctance to do - and I would be in favor of that reluctance - is calling someone a liar. Lying is an intentional state of mind, and it's very difficult to read somebody's mind."

It also goes back to Nyhan's point about making the correction persuasive. Using the word lie "can be far more inflammatory than it can be illuminating," Grimes said. "And I'm far more in favor of illuminating than inflaming."

Poynter's McBride disagreed.

"I believe that a deliberate distortion is a lie, and I think in this case there's no way to look at the original clip of what Obama said, and misunderstand his intent," she said. "So I'm comfortable calling it a lie, calling it what it is" - although, she acknowledged, a lot of other questionable political statements "don't meet that threshold."

"We can certainly say: 'This is a lie; here's the evidence that it's a lie,' and we can keep asking questions about who's responsible for the lie," McBride said. In fact, she said, "I think that there's a market for that."

Arianna Huffington wrote in a blog post Monday that she sees Romney's ad as "challenge to the media. It's like when a toddler looks right at you and slowly and deliberately spills a glass of milk. The child wants to see the reaction. It's a test of boundaries. If there's no reaction, then the message is that it's OK."

McBride concluded: "Democracy doesn't work if journalism doesn't work and journalism isn't working if falsehoods pervade the marketplace of ideas."

But isn't that exactly where we are already? Replied McBride, "That's my greatest fear."