"Freedom Riders": Lessons for a New Generation

[Source: PhilanTopic, by Kathryn Pyle, January 10, 2012]

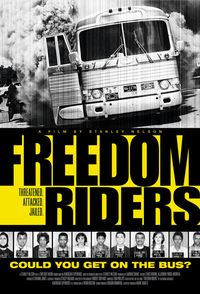

Writing from the 2010 Sundance Film Festival about the civil rights movement as captured in documentary films, I highlighted Freedom Riders, a documentary directed by Stanley Nelson that premiered at the festival. The film tells the story of the hundreds of courageous people, most of them young, who participated in the 1961 "freedom rides" that helped end segregation in the South.

Writing from the 2010 Sundance Film Festival about the civil rights movement as captured in documentary films, I highlighted Freedom Riders, a documentary directed by Stanley Nelson that premiered at the festival. The film tells the story of the hundreds of courageous people, most of them young, who participated in the 1961 "freedom rides" that helped end segregation in the South.Freedom Riders aired on PBS this past May; the film went on to earn three Emmy Awards, and the New York Times, calling it "beautifully constructed," selected it as one of the ten best programs of the year. The broadcast was preceded by a ten-day reenactment of the original 1961 campaign that was organized by American Experience, the PBS program that had commissioned and broadcast the film. "Get on the Bus" brought together forty college students from around the country to reenact the rides - from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans - and interact along the way with some of the original freedom riders, various historians of the period and community activists. As they made their way south, the kids shared their experience via Facebook, Twitter and other social media tools.

"The re-creation campaign had high visibility and great partnerships with state humanities councils, colleges and universities, and museums around the country," says Sonya Childress, community engagement specialist at Firelight Media, the nonprofit partner of Firelight Films, Nelson's for-profit production company. The former organizes audience outreach programs - a letter-writing campaign for Nelson's film The Murder of Emmett Till helped reopen a criminal investigation into that 1955 case - and supports emerging documentarians through a producers lab.

"'Get on the Bus' was very successful," Childress adds, "but we at Firelight wanted to do something different. We saw our job as bringing the film to a different audience - particularly youth, and including African-Americans, but people who weren't necessarily connected to the civil rights movement. In targeting youth groups, we immediately thought of the Dream Act, because the story of Freedom Riders is a story about multi-ethnic organizing. We wanted to reach people working on immigration reform who do not see the civil rights movement as part of their history or as relevant to their activism. And we wanted to help them use the film in their own campaigns."

Atlantic Philanthropies, the Open Society Foundations (through its Campaign for Black Male Achievement), and the National Black Programming Consortium were approached and ultimately funded the Firelight Media project.

"Many funders could have said the freedom ride reenactment was sufficient as an audience engagement component," notes Childress. "But these three organizations saw value in bringing the history to a new community. They understood that Firelight Films makes historical documentaries, but that we want to show that the lessons of the past can be dissected and discussed and applied to today. Also, the funders recognized that, being an independent entity, Firelight Media had the latitude to work with a wider variety of community groups than had been involved in 'Get on the Bus,' and that was seen as a complement to the American Experience project."

Engaging foundations that are not "media" funders is a new strategy for many documentary filmmakers; the challenge is in helping private and corporate foundations see that film can further their grantmaking priorities, and that there are many points of entry for support beyond a film's production phase.

At the same time, as foundations become more engaged in distribution, there is more concern around evaluation of the project's goals. In Social Justice Documentary: Designing for Impact, a new Ford Foundation-supported publication from the Center for Social Media, Jessica Clark and Barbara Abrash put it this way:

"In an environment of information overload and polarized sparring, social issue documentaries provide quality content that can be used to engage members of the public as citizens rather than merely media consumers. As a result, they have gained in visibility, influence and number over the past decade.

"But despite the box-office and critical success of high-profile examples such as An Inconvenient Truth or Supersize Me, the social impacts of such expensive, long-range projects have been hit-or-miss. As a result, investors and filmmakers are asking tough questions about how best to plan for and assess the impact of such films and related engagement strategies, and to create models and standards for a dynamic field...."

The report proposes a systemic approach based on early and continuous community participation that combines quantitative and qualitative indicators and continuous feedback into the evaluation design. The best indicators measure "evidence of [the film's] quality, increased public awareness, meaningful partnerships, increased public engagement and collective action."

Firelight Media's plan for Freedom Riders incorporated many of those elements, though as noted by the Center for Social Media report, each documentary project is distinct.

Firelight began by convening a small group of civic organizations to help develop ideas for a year-long project; by the time Freedom Riders was broadcast, the project was ready to go. (An agreement with American Experience required that the Firelight project not overlap with "Get on the Bus," which took place immediately before the film aired.)

Sixteen community-based organizations and student groups - some national and some local - were selected as formal partners. Seven of the smallest groups received stipends to carry out their activities. All agreed to screen the film and use an online guide, United in Courage (available on the Firelight Media site), to help plan events and facilitate discussions. Their experiences are being disseminated via an e-news broadcast to other partners, funders and filmmakers, and through Firelight Media’s newsletter; in effect, the partners provide ongoing feedback as a way to strengthen the project.

The groups include established organizations like the NAACP, which is bringing some of the original freedom riders to college campuses in the South for screenings and conversations. Puente Arizona has invited some of the freedom riders to discuss immigration reform strategies with members of the migrant communities with which it works. At a workshop on audience engagement earlier this fall in San Francisco, another partner, Bay Area-based Youth Speaks, described using the film at its annual Brave New Voices event, which brings young poets and youth development organizations together: five hundred spoken-word artists attended the screening and a subsequent conversation, later broadcast on Pacifica Radio, with two freedom riders. And New York City-based Brotherhood/Sister Sol showed the film in New York and Ghana and trained youth facilitators to lead post-screening talks. (A complete list of partners and their plans can be found on the "United in Courage" site.)

Recognizing that short films can be useful for community organizing and in educational settings, especially those involving children, Firelight Media produced a twenty-minute version of the film (available only to project partners) and also commissioned three ten-minute films on key issues in the current immigration policy debate. Immigration: Beyond the Headlines was supported by the Carnegie Corporation of New York and can be viewed on the Firelight Media site. Though apprehensive at first that the films would be seen as standalone media, Firelight staff now consider them to be useful vehicles for driving interested viewers to the longer and more comprehensive film.

Today, halfway through the year-long audience engagement effort, Firelight's independent evaluator is tracking how the full-length documentary is being used and the kind of impact it is having through pre- and post-screening interviews with various partners. The partners also submit formal reports on how they are using the film to enhance their work, in the process creating a repository of "best practices."

"Community organizations have varying levels of comfort with documentary films that are not 'advocacy' films, that are not prescriptive in terms of what to do about a particular issue," says Childress. "Freedom Riders is not a 'call to action'; it's an occasion for reflection. We're interested in knowing how community groups navigate that, how they challenge themselves and how they incorporate films into their programs. We want to know how this particular story resonates, especially within the immigrant rights movement that's looking for stories and trying to build relationships with other movements. The big question for us is: Can historical documentaries move the meter; can this content help people understand the current world?"

The anecdotal evidence is encouraging. Last month, as reported by the Montgomery Advertiser, "Two Freedom Riders who risked their lives to integrate Montgomery's bus station 50 years ago are back in the Capital City with a new cause: repealing Alabama's immigration law. The Rev. C.T. Vivian and Catherine Burks-Brooks joined a rally on the Capitol steps and a children’s march to the governor's mansion."

Some of the Firelight project's results to date are posted on its website in the form of testimony from the partners. We'll check back at the end of the year to see what lessons were learned and how they can inform the marriage between documentary film and community activism.